As a young sportswriter interning in 1980 at the afternoon newspaper in Winston-Salem, N.C., the now long-expired Sentinel, I didn’t have many lead-story assignments. My clips from that summer included pieces on industrial-league softball, go-kart races and local junior tennis tournaments. Getting to cover a golf exhibition and clinic featuring Juan (Chi Chi) Rodriguez was a big deal.

Rodriguez was in his mid-40s, a year removed from the last of his eight victories on the PGA Tour but still one of the sport’s most recognizable and popular figures. The native of Puerto Rico did not disappoint that day at Greensboro’s Bryan Park, launching soaring drives with his ball teed up on a golf pencil and smashing a ball inside a paper cup about 200 yards with a 3-wood.

As was his way, the trick shots were broken up by quips. “My luck is running so bad,” Rodriguez told the crowd, “my twin sister forgot my birthday.”

His golf fortunes turned around after Rodriguez turned 50. He was a mainstay on the Senior PGA Tour during that circuit’s most successful period, winning 22 times between 1986 and 1993 against the likes of Gary Player, Lee Trevino, Jack Nicklaus. Long after he won the last of his senior titles, he would still sign many autographs and make fans smile with his signature sword dance after making a putt.

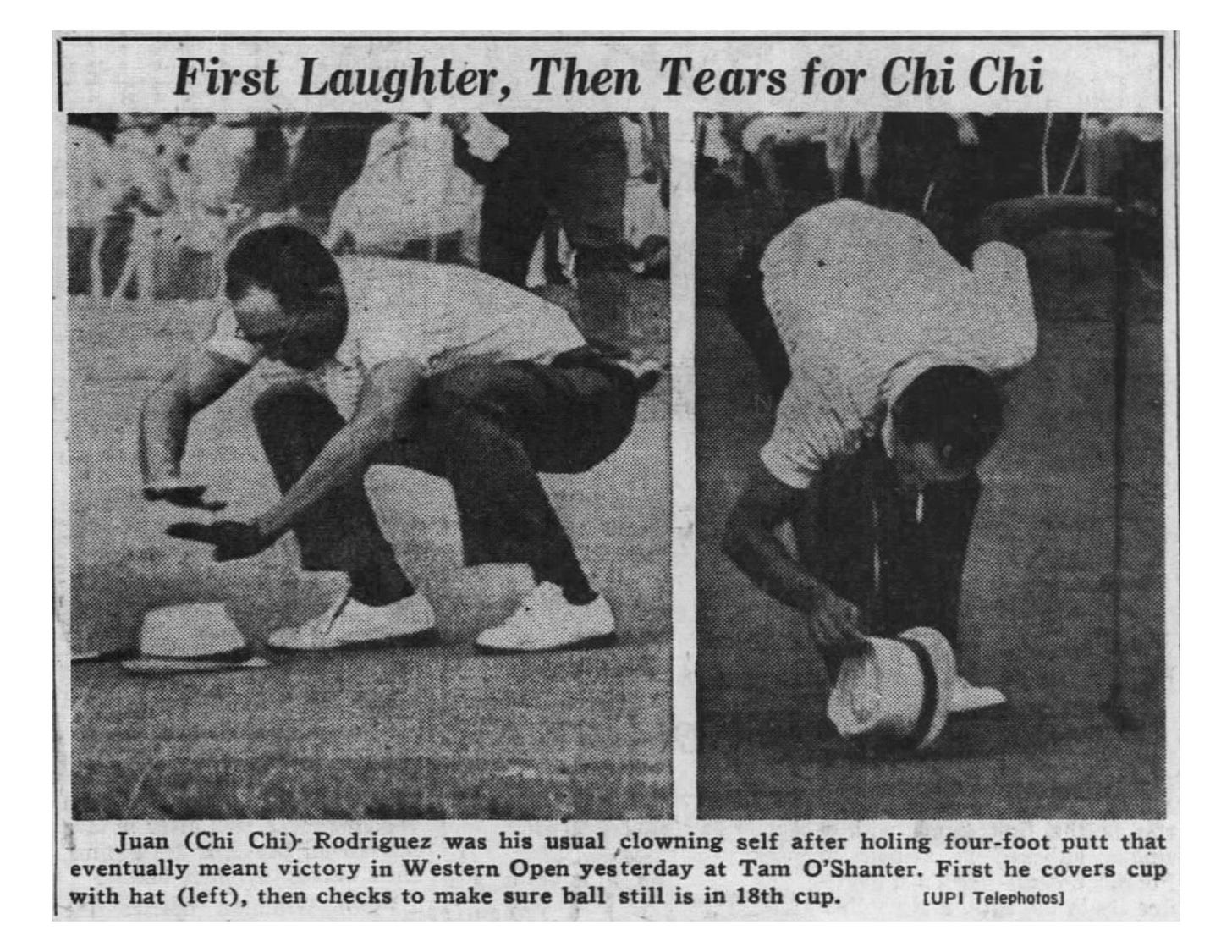

Rodriguez died Thursday at age 88, a day short of 60 years since he beat Arnold Palmer in the Western Open, the biggest of his regular wins. He stood 5 feet 7 and was reported to weigh 124 pounds that week, a time when he still celebrated putts by placing his hat over the cup, a practice that annoyed some of his fellow pros and gave way to his enduring—and endearing—matador act on the greens.

Chicago Tribune coverage of Rodriguez’s 1964 Western Open victory.

“The sword dance is a drama,” Chi Chi explained in Golf Digest in 2003. “I am a matador. The hole is a bull. When the ball goes in the hole, I’ve already slain the bull, so the sword fight with the putter isn’t necessary except to flaunt my skill. I wipe the blood from the sword with my handkerchief and return the sword to its scabbard. Then I go to the next hole and look for another bull.”

That Rodriguez could be in the position to celebrate success at golf’s highest level was remarkable. He grew up poor, cutting sugar cane like his father. His obituary in The New York Times included one of his humorous takes on those days. “I was so poor when I was starting out, I mean I had a room so small I couldn’t even change my mind.” His life might have been much different had he not gotten into sports as a kid—baseball, then golf.

“There was a small barren parcel of land nearby that served as our field,” Rodriguez wrote in 2017 for La Vida Baseball. “The bases were sheets of white school notebook paper affixed with twigs at each corner, forced into the ground by rocks. Running around the diamond barefooted, we gingerly tapped a toe on each base, all the while daydreaming we were sliding into them instead … Gloves were fashioned out of small brown paper bags that had once housed a half pound of beans, with five holes strategically and carefully placed and punched out of the bottom half.”

Rodriguez got his nickname because as a youth he pretended to be a Puerto Rican baseball player, Chi Chi Flores. It stuck and became one of golf’s most familiar names after he advanced from his very rudimentary beginnings in the game—a limb off a guava tree for a club and a small metal can hammered into a roundish shape for a ball—into a tour-caliber golfer.

Established professionals Ed Dudley and Pete Cooper saw Chi Chi’s talent and his gumption, supporting him with encouragement and instruction that he relied on to become skilled enough to play golf for a living. He never made much of a mark in major championships—a tie for sixth in the 1981 U.S. Open his best result—but always drew a gallery because of his flair. He received the USGA’s Bob Jones Award for his contributions to golf, and in 1992 was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame. Decades before there was a First Tee, Rodriguez did his part to assist youths who needed a helping hand.

“When you enjoy life and can bring about a few smiles and laughs, that’s what it’s all about,” Rodriguez told me in 1980. “It’s no fun to play when you’re putting bad, but you know, it’s better than cutting sugar cane.”

One of Chi Chi’s wins came at Greensboro, in 1973, when what is being played this week at Sedgefield Country Club as the Wyndham Championship was simply the GGO, Greater Greensboro Open. A sword dance of celebration on the 18th green by the winner would be fitting, a tribute for a distinct golfer who did it his way.

Wonderful piece, Bill. Chi Chi was among the great corps of players Peter Jacobsen recruited to play in the inaugural Fred Meyer Challenge at Portland Golf Club in 1986. Peter, as you know, was Chi Chi-esque in his skill and humor doing clinics of the kind you mention covering. I remember Chi Chi teeing up two balls and hitting them with an iron in quick succession, the first with a lurching fade and the other with a snappy draw, and while my memory has them colliding I think they just crossed in very close proximity. A very entertaining guy, but as with Calvin Peete, a throwback to a day when a poor self-taught player could succeed at the highest level. Sorry those days are gone.