Billy Burke's singular achievement

Ninety years ago, the Connecticut golfer prevailed over 144 holes in a one-of-a-kind U.S. Open

Despite the big differences between the generations in most areas of golf, achievements of one era often can be repeated at a subsequent time if talent and circumstances align. Someone could do what Bobby Jones did in 1930 (calendar year Grand Slam) or what Tiger Woods did in 2000-01 (four consecutive major wins). But the 1931 U.S. Open is a stubborn exception.

Nobody will ever win the national championship in the manner of Billy Burke 90 years ago this week.

Tournaments aren’t even decided by 18-hole playoffs anymore—it’s either sudden death or an aggregate format of a couple of holes—so the fact that Burke had to go through two 36-hole playoffs following 72 holes of medal play to defeat George Von Elm at Inverness Club in Toledo makes his achievement the ultimate outlier.

“Apparently they are going on forever,” Grantland Rice wrote in his syndicated column after the first playoff. “After the most sensational 36-hole playoff in the history of golf, they are still tied up in a two-ply Gordian Knot at 149 strokes each. There were enough fireworks in this contest to make the fall of Pompeii look like a single Roman candle.”

Hyperbolic to be sure, but Rice had a point. There were 25 lead changes over the 72 playoff holes. After making a birdie putt on the 72nd hole of regulation, Von Elm did it again on the 36th playoff hole to force another long day.

Burke’s count that early July week in Ohio: 144 holes, 589 strokes, 32 cigars, a one-stroke margin over Von Elm. The winner did it in scorching heat—there a number of heat-related deaths in the area—and on the heels of 72 holes of Ryder Cup qualifying and 72 holes of match-play competition in late June as . When Burke set out for Niagara Falls and a delayed honeymoon with his wife, Marguerite, after being the last man standing at Inverness, he had played 288 holes in 16 days.

It’s well known that Burke was the first golfer to win a major title with steel shafts in his clubs (Von Elm was still using hickory), but he also did it with a lighter, 1.55 ounce ball that the USGA had mandated for that season to put more challenge into the game. Like the 36-hole playoff format, the lighter ball was gone after 1931.

Burke was born in 1902, the same year as Jones and Gene Sarazen. William John Burkowski grew up in Naugatuck, Conn., and like Eugenio Saraceni came from a working-class family. “He impresses me as a player who has learned his game through a lot of hard work," Jones wrote in the The American Golfer, "as contrasted to one who has come by it easily and naturally." John Kiernan of The New York Times observed that Burke was “a square-shouldered stalwart who might pass as pugilist or a heavy-hitting second baseman.”

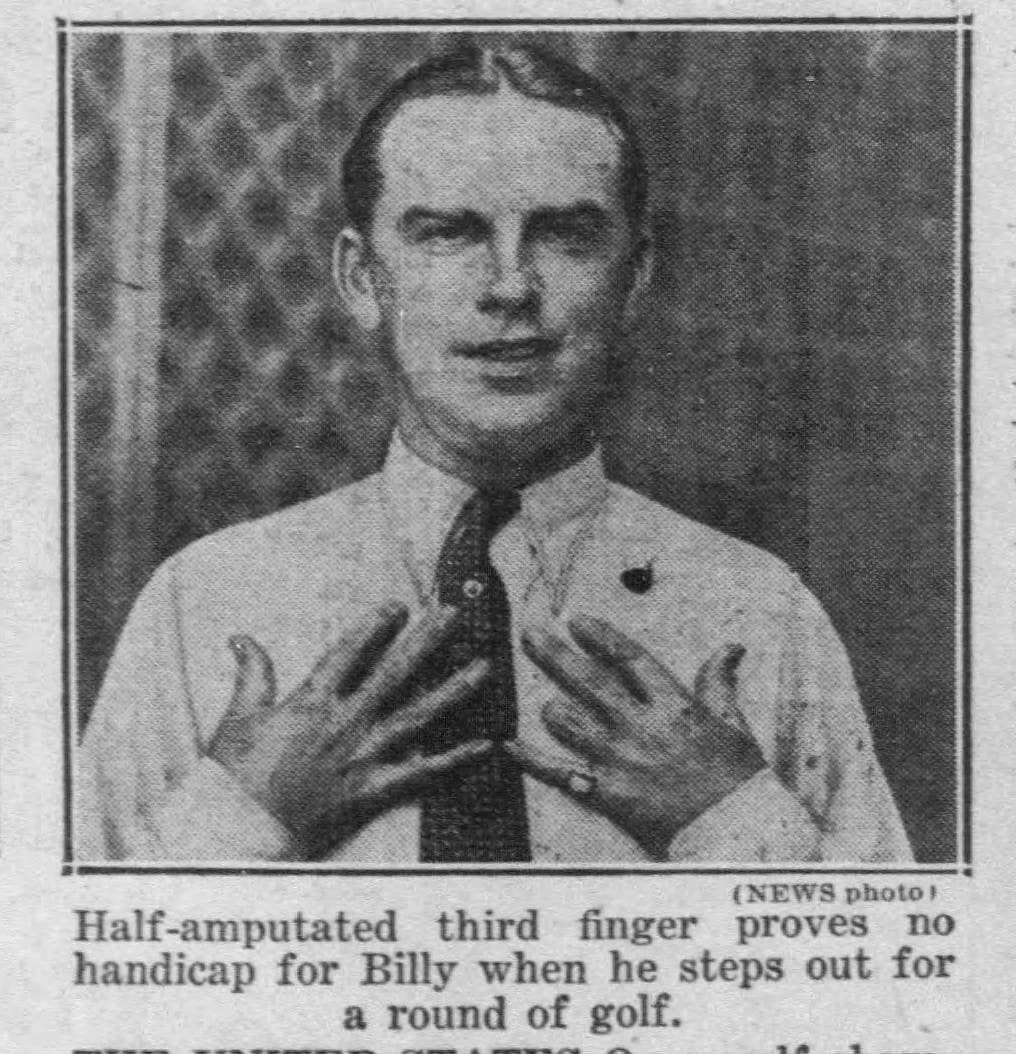

Burke succeeded at golf despite a disability from an accident in an iron foundry. (The New York Daily News)

Burke did wear a small glove on his left hand, an accommodation for a disability after an accident at an iron foundry as a teenager cost him parts of two fingers. Having gotten exposed to golf as a young caddie at Naugatuck Golf Club (now Hop Brook Golf Course), Burke also toiled at other jobs including an office janitor and at factories making boots and safety pins before becoming a golf pro. For Burke, playing a sport for a living—even a marathon championship in the heat—really was a “golden grind,” to use Al Barkow’s wonderful term from his important 1974 history of the tour.

Following his U.S. Open victory, Golf Illustrated predicted Burke was “a new star who is destined long to shine.” Credited with 11 PGA Tour victories, Burke didn’t win another major title but had two third-place finishes in the Masters (1934 and 1939) and put up an admirable defense of his U.S. Open victory in 1932, tying for seventh.

The man who prevailed in a 72-hole playoff died in 1972, at age 69.